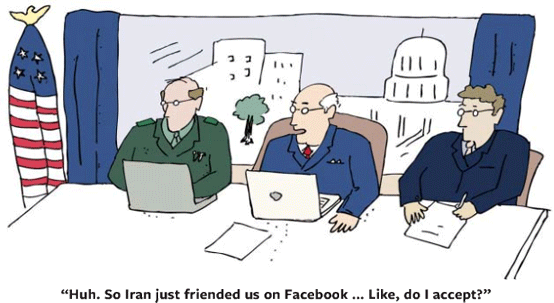

From Reader’s Digest, the challenges of Facebook Diplomacy.

Special thanks to Molly Moran (and her Mom) for sending this to me.

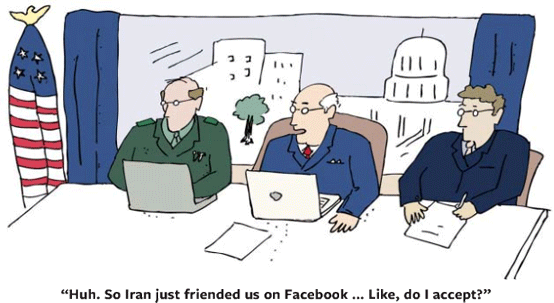

From Reader’s Digest, the challenges of Facebook Diplomacy.

Special thanks to Molly Moran (and her Mom) for sending this to me.

[image src=”http://www.darrenkrape.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/smith-mundt.jpg” caption=”Photo by Yael Swerdlow” align=”left”]

This post grew out of the recent Smith-Mundt Symposium, though since the conference was about a month ago, it is a bit late to the party. Several individuals have already written good summaries of the day’s discussion, so I direct you to those first.

That being said, there are a few points relating to the general conversation on Smith-Mundt and public diplomacy/strategic communications that are worth making (or reiterating).

First my general read-out of the event is that the issue remains quite contentious and with little overall agreement. Many argue the law should be kept, or even strengthened (and its remit expanded to the entire U.S. government) while others argue it should be completely repealed. A third group feel the argument is pointless since the law is out-dated and should be ignored, which can be done since, in the end, there are no “Smith-Mundt police” to arrest anyone for violating the law.

Smith-Mundt is a multi-faceted piece of legislation, dealing with the structure of public diplomacy, creating cultural exchanges, as well as the much argued ban on domestic distribution. Since the latter restriction has become the most contentious part of the act, I will focus my summary and comments here.

Last week, Marc Lynch (also known as Abu Aardvark), an associate professor of political science and international relations at The George Washington University and well-known writer and blogger about the Middle East, gave a fantastic presentation to my bureau at the State Department. He was kind enough to allow me to summarize his presentation and share it with the wider community.

Last week, Marc Lynch (also known as Abu Aardvark), an associate professor of political science and international relations at The George Washington University and well-known writer and blogger about the Middle East, gave a fantastic presentation to my bureau at the State Department. He was kind enough to allow me to summarize his presentation and share it with the wider community.

His presentation, and the following discussion, focused on his personal experience as a blogger, including his engagement with counterpart bloggers in the Middle East, and on the general history and landscape of blogging in the Middle East.

This is the first of a planned series on the use of social media in the 2008-2009 Israel-Gaza conflict, largely derived from the examples and articles I’ve collected over the past few weeks.

The Israeli Consulate in New York recently held the first Twitter-based press conference. While it was an interesting experiment, the technology was poorly suited for this sort of activity (read two good critiques from COMOPS and Columbia Journalism Review). As Rachel Maddow pointed out, they were trying to explain a conflict in 140 characters that authors have struggled to decipher in books. Many critiques have been written on this, so I will highlight a counter-example where Twitter proved an excellent medium for delivering press-type engagement.

Sean McCormack, the State Department’s spokesman, twittered (and photographed) his way through the recent negotiations and vote on the UN Security Council’s Gaza cease-fire resolution. His tweets noted the negotiation process all through to the final vote, which passed with the U.S. the lone country abstaining. His updates were interesting on their own, conveying a sense of insider information and a direct connection with the process.

What I found more interesting though, was immediately after the vote, several people asked McCormack, via Twitter, why the U.S. chose to abstain. At this point, the mainstream media had only just reported on the vote and provided little additional context (and none had explained the U.S. abstention). He fired off a few quick responses, including:

“@kmcurry support ceasefire but wanted more progress Mubarak initiative before a vote. That said, wanted to get to ceasefire.” – link

While he didn’t get into details, expectations were low (unlike the consulate event) and because this was so impromptu and immediate, a handful of sentences were all that was needed. More detailed explanation could come later. His quick replies really gave a real sense of openness, engagement and immediacy. Naturally, scale helped a lot here, this was informal and he probably only received a dozen questions (if that), most on the decision to abstain.